Tropical hardwood beams, locally-fashioned framing connectors, and mahogany siding. Who needs a view?

We call our tiny-house plan the Cisterna Cottage because it’s built on top of the neighborhood water tank, or cistern

In the old days, a cistern was an underground tank used to hold rainwater for household use. Our cisterna is filled with the low-pressure municipal water that comes in fits and starts. By saving it in a big, concrete tank, we get both reliable water, and good pressure. Yet the big old tank is an eyesore and takes up valuable beach-front real estate. So, we decided to build atop the tank to hide it.

The house we’re framing measures 5-meters by 5-meters, or roughly 270-square feet. Once we had a suitable set of plans, drawn by a talented Ecuadorian architect, Rogelio Coque, the next step was to start building. No need for meddlesome municipal permits and inspections, it’s Ecuador.

And it’s going to be a wood house, so construction means carpentry. We need lumber.

Buying Lumber

Air-dried lumber in Ecuador is stacked with spacers between each piece to allow air to circulate. Air-dried woods generally contain about 20% moisture. Kiln-dried woods generally contain less than 15%.

The lumber we bought was purchased about two years ago and air dried. There’s a business in Ecuador in buying green lumber from the mill, then letting it set in a drying tower, with spacers between the planks, and then selling it a premium.

Yup, someone should build a lumber kiln, but to date, nobody has. As in most of the world, masonry and concrete are the materials of choice here in Ecuador, so the tradition of wood framing and siding has not evolved. Folks are skeptical of wood, softwoods especially.

In time, when we try to sell, having built from wood may prove a market challenge.

To help mitigate the skepticism, our contractor, Javier Gonzales, insisted on using only the very best hardwood, chanúl (Humiriastrum procerum), a lesser known tropical hardwood of extreme structural characteristics.

The chanúl trees grow tall and straight, reaching heights of up to 115 feet, with trunk diameters of up to four feet. They come from the Esmeraldas region of Ecuador, near the Colombian border.

The lumber is used for railroad car construction, boat building, hardwood flooring, furniture and turned pieces, like balusters and furniture legs. We were going to use it as framing lumber.

Figueroa tree from Wikipedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Andirobaamazonica.jpg

Our siding would come from the gorgeous and insect-resistant Figueroa (Carapa guianensis), a local hardwood that resembles mahogany, growing in rainforests about 20 minutes away from the jobsite.

Mostly used for fine furniture, we would use it as clapboard.

Our Figueroa clapboard is full dimensioned plank—like a thick steak, meaty. Our doors and millwork would be made from saman and guayacan, noble hardwoods that we’ll talk about later.

I picked up Javier near his home in Libertad, and we drove to the lumber yard. It’s really a forestry company outlet. Most of the forests are exploited by small time lumberjacks that cut a handful of trees every year on ancestral land. They take the lumber to an acopio, or collection center, where the mill purchases the tree trunks from the lumberjacks and slices them into large beams that are then distributed to local lumberyards.

At the yards, they cut the lumber on table saws, dry it, plane it, and then sell it to the public.

At the Libertad lumber yard, the manager, Oswaldo, gave me a quick tour of the facility, showing off their shaper, table saw and planer. They take large beams and cut them down to customer specifications. They build doors and some trim profiles. He showed me the many varieties of wood available, none you’ve ever heard of, except maybe teak.

Some people frame with teak – imagine that.

Slicing lumber on a table saw at the lumber yard.

Unlike the lumber in the United States, we don’t have stock sizes to choose from in Ecuador, we had to dimension our lumber and have it milled to suit. I wanted to use gringo joist hangers because the locals notch joists to hang off the ledger, and this weakens the lumber.

So, we had our joists milled to 1.5-inches wide, for the 2x8 hangers I bought in the States, and our posts were milled to 3.5 inches to use my gringo post anchors. I also bought a box of A35 clips for all-purpose connections, not realizing just how popular they would be with the local carpenters.

Javier loaded up the truck and left for the jobsite.

Rough Carpentry, Southern Style

Sanding lumber under the shade structure.

After the first load of framing material arrived, Javier set his crew to work under the shade structure, sanding the boards. I had never seen a framer clean and sand the lumber before building, nor had seen such straight, dense, reddish lumber on a construction site.

I felt like we were about to build a cabinet, not a house.

The structure the carpenters began building resembled a modified post-and-beam building, with balloon-framing posts standingt o the full height of the structure, hanging beams between the posts, and relying on cross bracing and the wood siding for stiffness.

I’m not sure the structure would pass inspection in USA.

Tight cuts with putty

Nonetheless, our Ecua-carpenters they were very conscientious about their work, setting levels with a traditional water level, and using wood chisels to nudge connections precisely.

They even puttied nail holes and joints—framers!

House framed with hardware visible.

You’ll note in the picture how much hardware we used. This was not my intention, I’d bought just enough joist hangers to hang our balcony joists off a ledger bolted into the walls of the cisterna. And about 50 A-35 framing clips, just in case they needed to tie something together.

Instead, the carpenters began using framing clips on every connection and ran through the 50 pieces in no time.

Ecuador-made framing clips

Javier called me, and said, “Jefe, we need more of those metal things.” I can’t go back to the states just to buy another box of framing clips. No problem, Javier replied. He went had 100 of them made at a local blacksmith’s. They cost him $0.98 each. In the USA, I’d paid $1.69 apiece.

In the picture, the A-35 at the very bottom is from the USA, the rest were made in Ecuador.

Sorry Simpson (the US hardware manufacturer), there’s no patent law here!

For the bathroom walls we used concrete block, since we would finish the room with ceramic tile.

When the joists were set for the sleeping loft, Javier called and ask me to drive down to the beach and enjoy our future views.

Our land is peninsula that juts into the Pacific, and just a story and half above grade, we have 180-degree views of the ocean.

But I could not help staring at the beauty of the beams.

For lunch, the guys sometime fish from the edge of point, catching ocean catfish they stew. I didn't’t know ocean catfish existed.

When I was looking at the wood pile, I noticed many of the boards and most of the larger beams had what looked like a decorative cut, almost like a corbel end. Javier explained that the notch was put into the ends of the tree trunks felled, so that they could tie the rope off and have the mules drag them out of the forest.

I hope to see that someday.

Siding with Mahogany

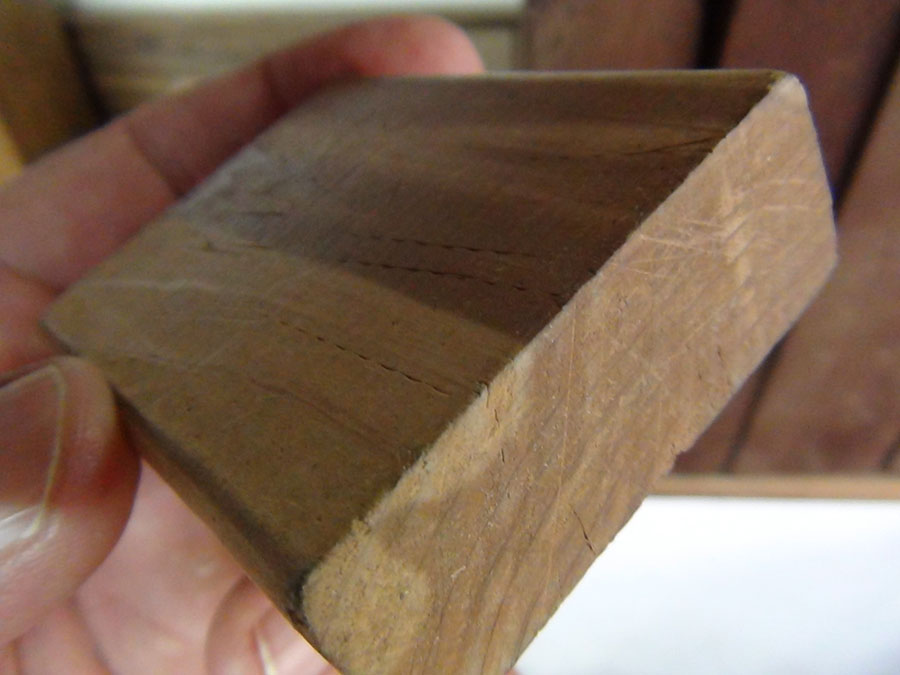

Figueroa is not actually mahogany, but in the same family of hardwoods, and used for similar purposes, high-quality hardwood furniture. You can see, we use it for clapboard, but look at that rich color. You can imagine what it will look like finished.

Overall, the quality of the wood we’re using reminds me of the California cottages I remodeled many years ago, framed with old growth redwood. I hope the spectacular forests of Ecuador don’t go the way of our California redwoods. The government keeps an eye on illegal logging and everyone assures me the lumber we use was harvested under the strictest standards of sustainability from certified forestry operations.

Yet I know a twenty-bill will buy you a permit, and enforcement is lax, so I’m never too sure.

Next: Cutting Rafters

The carpenters cut a hip roof much the way we do it in the USA. The sheathing will consist of Figueroa strips spaced about three centimeters apart, an airy base for the toquilla (not tequila) thatch to go over. The roofer is busy working on making the thatch, and he and his family have been working about two weeks already at his base in the rainforest.

I’ll take you there soon.

This article is part of an ongoing series, Work in Progress: Vistas del Pacifico, on constructing homes in Ecuador

— Fernando Pagés Ruiz is ProTradeCraft's Latin America Editor. He is currently building a business in Ecuador and a house in Mexico. Formerly a builder in the Great Plains and the Mountain States, Fernando is also the author of Building an Affordable House and Affordable Remodel (Taunton Press).