If drywall were clear

We'd see walls get wet daily

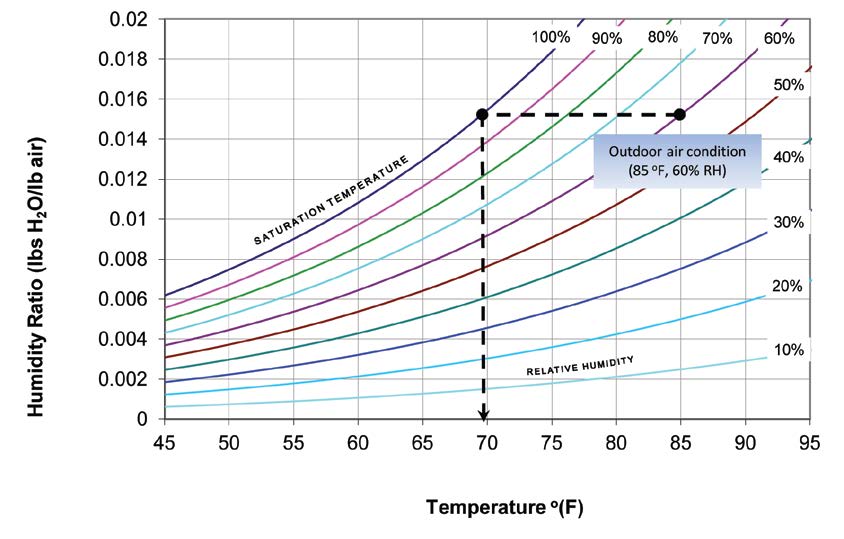

Moisture rides on air

This photo is obviously of a window and storm window. But let's think about it for a minute.

- Let the storm window represent the exterior sheathing.

- Let the air between the windows represent the insulation layer.

- Let the inner window represent the drywall.

The insulation layer is doing a good enough job of keeping the drywall from getting too cold. The exterior sheathing is the coldest part of this assembly, the drywall is the warmest. The temperature goes down linearly between the two layers.

How did so much ice make it into the wall cavity?

Air leaks.

Moist air from inside sneaks into the wall cavity through electrical outlets, gaps in the drywall, poorly detailed interior soffits, and other places (bad window glazing, in this case).

The moisture condenses on the cold surface (the exterior sheathing in the case we are imagining) and freezes. When the sun comes out, other ice melts and drips down to the bottom plate of the wall. The next day, the same thing happens. Come spring, there is potentially a lot of moisture in the wall that needs to go somewhere and do something.

If this is a leaky old house, the moisture will escape and the wall will dry.

If this is a semi-tight assembly, the moisture will sit in the wall cavity.

If it is a very tight assembly, the moisture never gets into the walls, so it's a moot point (but if it did, it would never escape, so it's not a moot point).

Touché

It is important to design and build walls that can dry without leaking.